By Noeleen Timbery

As we draw closer to the 250th anniversary of the Endeavours’ arrival into Kamay (Botany Bay), there has been a shift towards a new perspective on this historically significant event. The perspective I am referring to is the view from the shore. This view covers the significance of the arrival and departure of Cook, both in itself and as a precursor to colonisation, to the Aboriginal people who witnessed these events. Acknowledging this view from the shore is important as a matter of historical accuracy as well as a long overdue recognition of the descendants of this people who, as you would have seen from previous editions of Stories from the Shore¸ continue to live and work on their traditional country of Coastal Sydney.

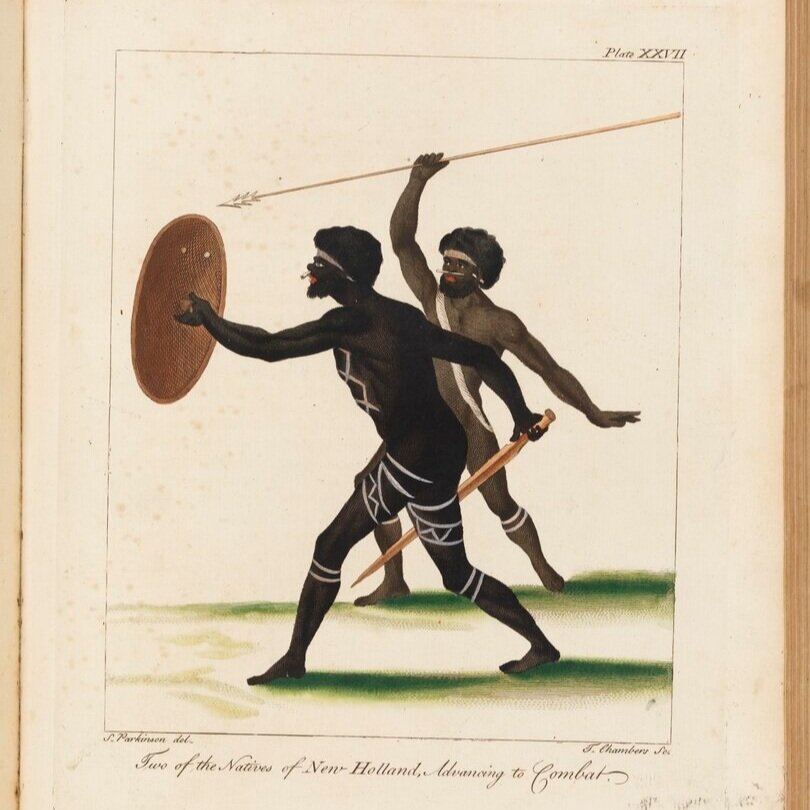

Two Natives of New Holland Advancing to Combat Sydney Parkinson - State Library of NSW

There are many stories within the Aboriginal community of La Perouse, the only Aboriginal community with a traditional connection to Coastal Sydney, of the landing of Cook. Stories have been passed down through family stories retelling the events of 29 April 1770 and the days that followed. However the retelling of this history, in an environment heavily impacted on by colonisation requires careful and informed considerations.

The retelling of Aboriginal history in the colonial setting has been prominently told by non-Aboriginal academics relying on colonial records. Most of this work is not validated against cultural information and does not recognise the limitations of the colonial records. The most substantial limitation is that most colonial records were recorded by the coloniser through a Western lens. This has resulted in non-Aboriginal academics making assumptions which are published without disclaimers and then become accepted as “truth”.

These mistruths may seem trivial in isolation and many academics treat them as such, often moving onto a new topic which interests them. However, for us, there is much more at stake. Misguided assumptions on the behaviours, movement and identity of Aboriginal people at the time of Cook’s arrival can have long-lasting effects on their descendants to this day. In addition, attempts by Aboriginal people to correct mistruths based on western assumptions are often hampered by the absence of an academic pedigree or the dismissal of oral histories as inaccurate.

This issue reared its head in May 2017. In my capacity as Deputy Chairperson of the La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council, which is the peak representative body for Aboriginal people with a cultural connection to Coastal Sydney, I was invited to attend a meeting at the British Museum. The purpose of this meeting was to discuss the spears and shield which were alleged to have been collected by Cook’s expedition after they fired upon the Aboriginal men who challenged them on the shores of Botany Bay.

Uncle Rod Mason, Senior Leader of the Gweagal Clan teaching children how to make a garrara or fishing spear at Kurnell 2019

At the same time, there has been a highly publicised campaign for the recently termed “Gweagal Shield” to be returned to the rightful owners. A descendant of an Aboriginal man Cooman led this campaign and has received widespread support from all levels of society with some notable exclusions. These exclusions were the Gweagal Clan themselves and those with a continuous connection to Coastal Sydney based at La Perouse. These important stakeholders do not endorse this campaign and to this day have never been consulted in a meaningful way. It should also be noted that this campaign is being run from a far south coast town more than 350km from Kurnell.

The obvious question is, how did a campaign built on such shaky foundations receive so much support? The answer is twofold.

Firstly, there was the promotion of a slight mistruth as described earlier in this article. In 2006 the State Library of NSW held an exhibition Eora Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770-1850 promoting the events that took place on 29 April 1770 by stating “the Aboriginal man at right, armed with a shield, a woomera (spear thrower) and a fishing spear, might be Cooman or Goomung, one of two Gweagal who opposed Cook’s musket fire at Botany Bay”. A closer look into underlying sources shows that the assumption that it might have been Cooman that met Cook that day is nothing more than an assumption at best, with a number of more feasible candidates present within the oral histories kept by Aboriginal families belonging to the area. In addition, the caption for the exhibition, despite using the term “might be”, has become the “truth” in some circles.

In addition, no one who decided to throw their support behind the campaign bothered to check whether the Gweagal Clan or any other Aboriginal person with a continuous connection to Botany Bay agreed with this approach. That isn’t to say that they don’t want the objects stolen from their ancestors back on Gweagal country. However, the fact of the matter is that public protests demanding the return of objects held by the British Museum is not always the best approach (as seen by exchanges with Egyptian and Greek governments). There was also a notable lack of queries as to why this campaign was led by those residing on the far south coast as opposed to senior Gweagal people who have maintained a continuous connection to Coastal Sydney.

In summary, this misinformed caption and willingness to overlook knowledgeable Aboriginal people and their connection to country is the basis of the Gweagal shield campaign.

The next question is, how can we make sure this kind of situation doesn’t arise in the future? In my view, the answer is simple. Approach our history with an inquisitive and open mind. Inquire as to whether historical accounts have been warped by a colonial lens and be open to Aboriginal histories as reliable sources which can help complete our shared history. These rich sources are present in every Aboriginal community with a connection to the country on which they stand. All you really need to do is ask and then, most importantly, listen.