By Ash Walker

I think it’s safe to say that the Sydney Fish Market is an institution. I remember going there as a child and, after navigating the interesting smells wafting around the carpark, being amazed by the array of seafood from around Australia and beyond. However, it wasn’t until I was much older that a senior man from my community asked me if I knew the origins of the Fish Market. It was only after that conversation that I was aware of the pivotal role my people, the Dharawal community based in La Perouse, played in the early stages of the colony that would become Australia.

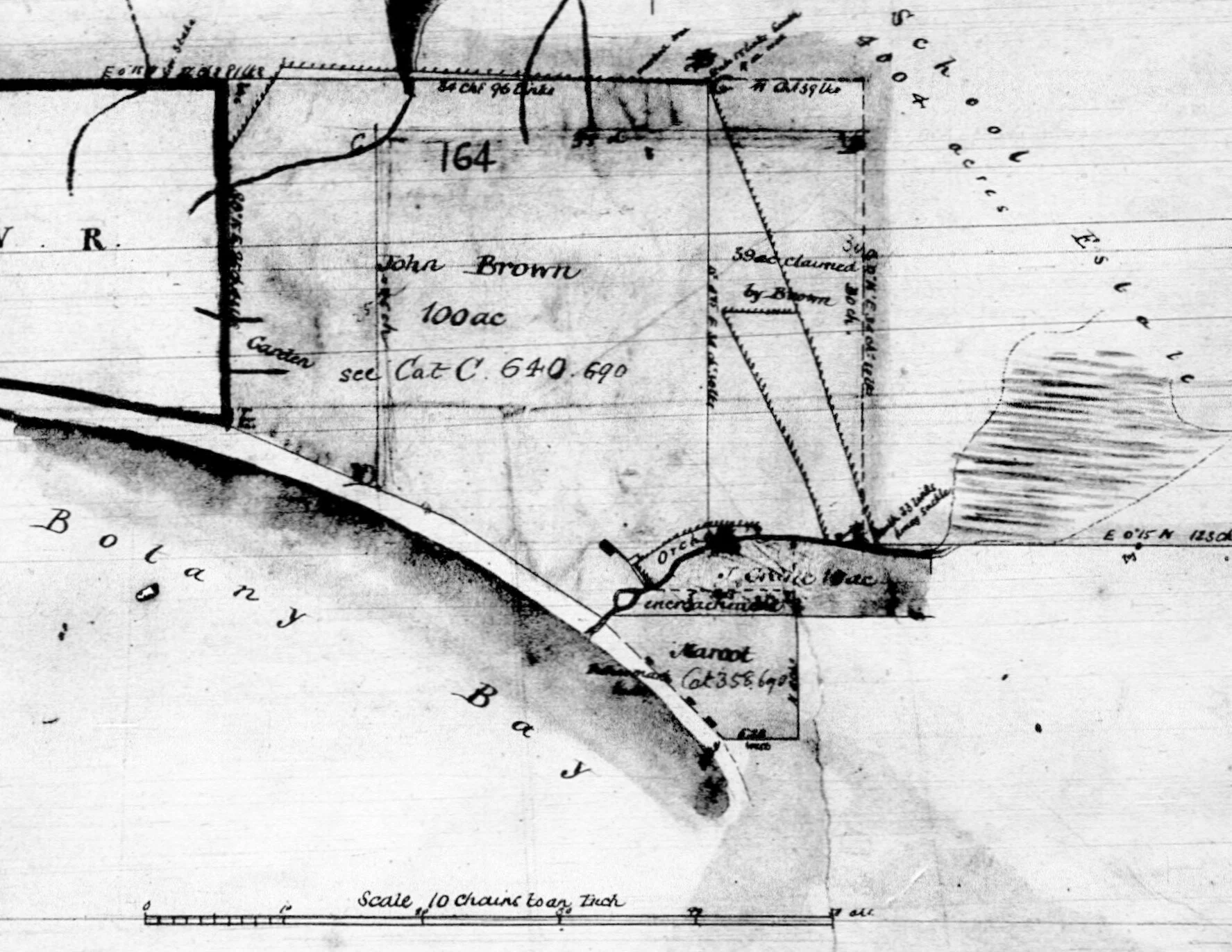

Botany Bay Aboriginal man Mahroot owned a life time lease of land at Botany (pictured above). Mahroot leased fisherman huts and operated a successful fishing business on ‘his’ land. State Library of NSW

Let me take you back to the late 1800s. The Sydney colony was growing. It had started as a meagre settlement at the Rocks but has begun to expand west along the Paramatta River. Despite the fact that European Settlers had been steadily claiming Aboriginal owned land, relationships with the original inhabitants of Coastal Sydney at this time were broadly positive. This was demonstrated by that fact that local Aboriginal people moved freely and engaged in the economy of the colony, even spreading rumours of cannibals to the south of Botany Bay in a bid to drum up business for paid hunting trips in this region (aggressive marketing at its best!).

This situation changed in 1883 when a man by the name of George Thornton used the drowning of a young Aboriginal boy living in the Sydney Boatshed (which is now the Sydney Opera House) as the catalyst for establishing the NSW Aborigines Protection Board. The first act of this new body was to round up every Aboriginal person living in places such as the Sydney Boatshed, Elizabeth Bay, Rose Bay and numerous camps around Botany Bay and forcibly move them to La Perouse Mission on the northern head of Botany Bay. My grandmothers’ great grandparents were living on the northern head with four other families at the time.

The next step taken by the Protection Board was to provide regular rations to those confined to La Perouse Aboriginal Mission. However, the Protection Board was surprised to discover that the Aboriginal people living there rejected the rations. This prompted an investigation which revealed that, in the then fertile waters of Botany Bay, my Aboriginal community was operating a commercial fishing fleet! The business model was, once they had fulfilled their cultural responsibilities by feeding the community, excess fish was delivered to the prominent colonial Wentworth and Hill families, with whom our leaders had strong relationships. The Hill’s and the Wenthworth’s then sold these fish from their estates within the colony of Sydney which provided an invaluable food source to the colony. Profits were split evenly between the Aboriginal community and their distributors, providing a meaningful income to Sydney’s first peoples. I am confident that this arrangement was one of the first, if not the first, of the many social enterprises launched within Australia since colonisation.

In my view, the next act of the Protection Board was so damaging that it is still felt by my community today. Realising that the income generated by the La Perouse Aboriginal commercial fishing fleet was greater than the combined income of the entire Protection Board, they decided to confiscate our fishing boats and nets. It was at this point that, against our will, we were forced into a cycle of welfare dependence. A cycle which we are still fighting our way out of this very day.

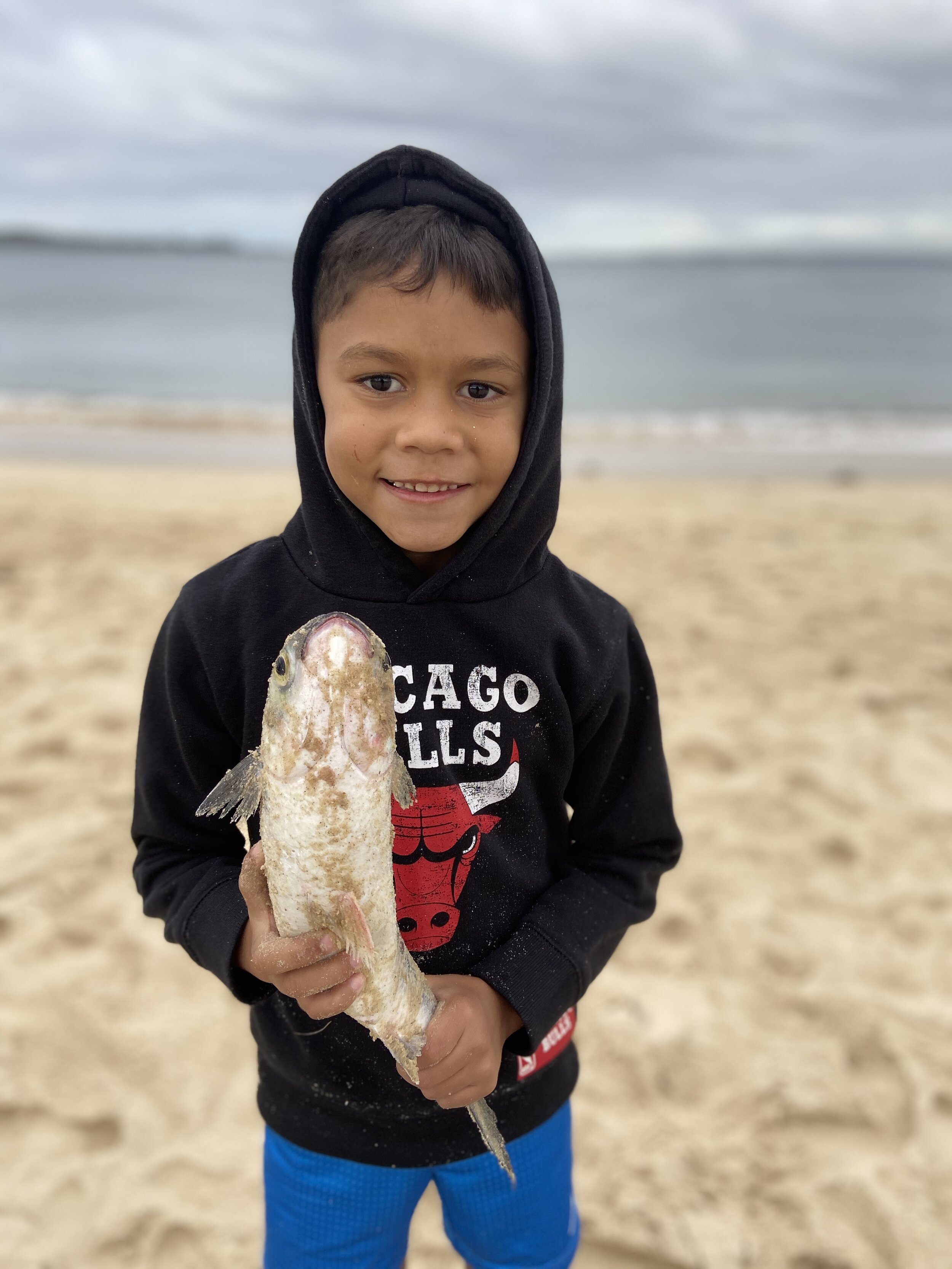

Leeton Ingrey, aged 7, holding a mara or mullet at Yarra Bay April 2020

Once the protectionism era ended, my community was once again permitted to engage in the Australian economy. However, we had been marginalised for so long that we were unable to afford commercial fishing licenses. We were reduced from market leaders in the fishing industry to criminals under government fishing laws should our catch exceed “legal” limits. Thankfully, NSW Fisheries now permits us to engage in cultural fishing which has meant that our people can haul seasonal mullet and once again fulfil our cultural obligations by distributing the catch to our community. However, Gamay is now overfished and overrun by industry, meaning that any opportunity to use our fishing skills to drag ourselves out of poverty has passed.

The thing that struck me most about this story was its contrast with the perceived relationship between Aboriginal people and welfare. As we had for thousands of years, my people adapted as the world shifted around them. We identified the need to earn an income and met that need any way we could. Significantly, it was the partnership with the Hill’s and Wentworth’s, free of paternalism, which allowed us to forge a path in this new world. It is my view that we must reach a level of economic independence before we are truly in control of our own future. Furthermore, our expulsion from the economy during the protectionism era means that, if we are going to reach this goal in my lifetime, it will be alongside prominent partners in modern Australia. It is my hope that together, we will be able to build a better world for my people, not by carving a new place in modern society, but by reclaiming our past position as a valued part of the Australian economy.

Gamay Rangers and community members pulling in a fishing net at Yarra Bay April 2020